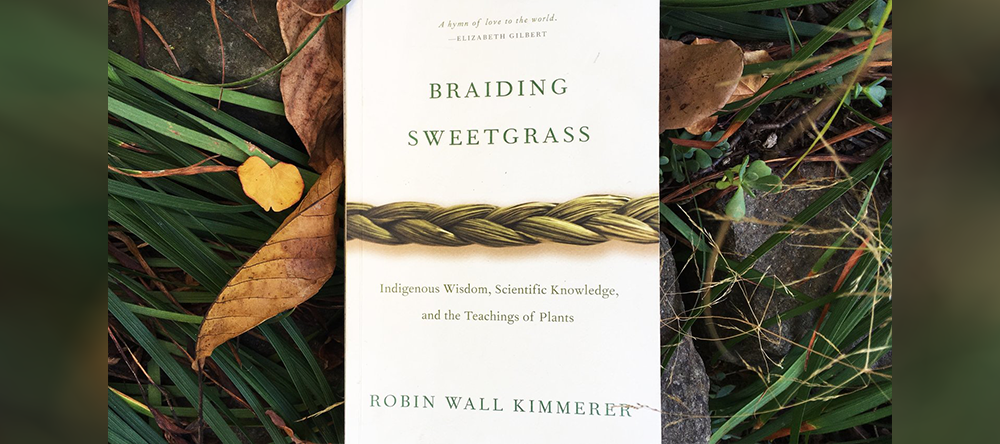

"Braiding Sweetgrass" woven with social and ecological justice for all creation

"In some Native languages, the term for plants translates into 'those who take care of us,'" writes author Robin Wall Kimmerer in her book, "Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teaching of Plants." Robin is a SUNY Distinguished Teaching Professor of Environmental Biology and the founder and director of the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment. Both FSPA Integral Ecology Director Beth Piggush and Justice and Peace Promoter Pat Ruda have read the book and offer their own perspectives of the social and ecological justice they found within the pages — those that call us to care for all creation.

Beth Piggush

"Braiding Sweetgrass" by Robin Wall Kimmerer is a book that has supercharged my senses to the Earth Community of people and planet. Robin presents this book as a gift of braided stories "meant to heal our relationship with the world" by weaving together the three strands of "indigenous ways of knowing, scientific knowledge and the story of an Anishinaabekwe scientist trying to bring them together in service to what matters most."

Two themes that resonate with me are ceremony and overconsumption. The significance of braiding sweetgrass, of ceremony, is symbolic of the philosophy and spirituality of the indigenous people. Sweetgrass is a sacred, healing plant to the Potawatomi people and is braided "… as if it were our mother's hair, to show our loving care for her." The author shares the meaning of becoming indigenous to a place, of how the land is the "real teacher." Often while reading, I was reminded of all the lessons I learned as a child playing outside, like the difference between a raspberry leaf and a nettle leaf. The methodology Kimmerer used with her ethnobotany students was meant to enlighten them to the fact that "The plants adapt, the people adopt." In addition, she elaborates on the purpose of ceremony and how "the community creates ceremony and the ceremony creates communities."

The author frequently references the Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving Address, the ritual that commenced all meetings in the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy. It begins, "Today we have gathered and we see that the cycles of life continue. We have been given the duty to live in balance and harmony with each other and all living things. So now, we bring our minds together as one as we give greetings and thanks to each other as people." In conclusion, those gathered would respond, "Now our minds are one."

The address honors the Earth, Water, Fish, Plants, Food, Medicine, Animals, Trees, Wind, Sun, Moon, Stars, Teachers and The Creator. And after each piece, everyone replies, "Now our minds are one." As Robin writes, "It is a lesson in Native science."

The rhetoric feels like some prayers I grew up within church — a call and response liturgy — but its goal is consensus. The more I saw this idea come back around in the course of the book the more I wished that a similar consensus was present in Christian cultures. There are daily intentions, traditional prayers and ceremonies of faith, but is there a respect and understanding that Christians have everything we need already?

The other theme that hit home for me is overconsumption, the parallels she draws between the indigenous people's stories of the Windigo monster and the greedy nature of mankind today that allows for the destruction of nature's structures, habitats and balance in the name of progress and profit. Our modern culture is this selfish behavior, our Windigo. Robin states that "we seem to be living in an era of Windigo economics of fabricated demand and compulsive overconsumption." In addition, "Our leaders willfully ignore the wisdom and the models of every other species on the planet — except, of course, those that have gone extinct. Windigo thinking."

Robin also braids together three different points of view with themes of reciprocity, the spirit of community, a gift economy versus a property (market) economy, gratitude and the four aspects of being — mind, body, emotion and spirit.

This is a beautiful book that resonates with me even more when I think about The Revolution of Goodness proclaimed by FSPA and the commitment to action to "build bridges of relationships that stretch us to be people of encounter who stand with all suffering in our Earth Community."

As the warm air starts to ascend on us and the gifts of Mother Earth come alive after a long winter sleep, I want to think I will be paying attention. And this mindfulness will sharpen my intention to action for our whole community. We can start to realize that when we take, we also need to give back ... we have reciprocal relationships with the planet, with people and with God.

Robin Wall Kimmerer writes that "the land is the 'real teacher,'" and FSPA land at St. Joseph Ridge is serving as such. Pictured in Jacoba's Greenhouse are Viterbo University nursing student volunteers Alexis Dubiel, Destiny Anderson, Carson Timm, Emily Bassler and FSPA Ecospirituality Project Outreach Coordinator Karen Stoltz who shared with them our ministry of ecospirituality firsthand.

Pat Ruda

"Braiding Sweetgrass" is a popular book read and reflected upon by religious communities around the country. This writing helps us understand the indigenous culture's sacred plant, sweet grass, and how the origins of plant, animal and human life on Mother Earth connect us all. Robin Wall Kimmerer is a trained scientist, decorated professor and a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, a tribe of indigenous people located in Oklahoma. The book is wonderful in many ways and can take us back to our childhoods gathering wild strawberries, tapping maple syrup, or even splashing around in a muddy pond.

I did not grow up with firsthand knowledge of indigenous cultures, only knowledge of what our history books taught us. When I read "Braiding Sweetgrass," I realized that I could connect with many of the stories and also gained a new appreciation for the beautiful culture that was introduced in the writing. I know that to understand others you must listen deeply to their words, and the author allows us the opportunity to do so. I am only beginning to understand some of the rituals and why they are so sacred to the indigenous people.

Sweet grass is a fragrant, holy grass known in indigenous culture as wingaashk, the sweet-smelling hair of Mother Earth. Breathing it in is said to stimulate memories. The braided stories are very compelling and bring together the notion of interconnection to Mother Earth. Another wonderful lesson that Robin brings forward is the idea to never take more than you need from nature. If you treat Earth well, it will be here to support and nourish you. I believe this is an important message for all of us that speaks to the protection of Earth against climate change.

If we look at this teaching in the social justice framework, we will begin to explore lifestyles, address consumerism and over-use of our natural resources. The question then becomes whether or not we see Earth as property or as a gift. If I choose to see Earth as a gift, I need to appreciate and respect its beauty that I have received. I will not take more than I need. This is the profound philosophy that Robin shares throughout the book.

"Braiding Sweetgrass" offers much room for discussion and certainly deserves to be read in our community to educate us with an appreciation for the culture and scared ways of indigenous populations.

Also in the March 2021 e-edition of Presence:

Sister Karen Lueck publishes book encouraging a different view of leadership

Finding "The Way" through universal values

You've been invited ...